DRONING THE FARM Robert Blair’s neighbors have grown accustomed to seeing him launch a small aircraft over his fields in Idaho. It’s a nice-looking little plane about 4 ft. long, with a wingspan of around 8 feet, that systematically flies back and forth over sections of his land.

What’s Blair doing with this thing? He runs a good-sized operation – 1,500 acres. It’s hard to know where and how much to be tending the crops on a spread this size. And the cost of tending them has risen dramatically as the costs of fertilizer, fuel and water have increased. So targeting areas needing attention, rather than broad application of expensive remedies, has become imperative.

He operates the drone from his laptop, which sends it flight path instructions. The drone is equipped with a digital camera that photographs his crops at high resolution and sends the data back in real time. Software in the laptop stitches the frames together for a continuous picture, like Google Maps. It takes about a half hour for his drone to survey a square mile of his land, and in a couple of hours or so he has a complete, very detailed picture of his crops.

With this, he quickly identifies a problem area and selectively adds more water, fertilizer or pesticide before the problem grows. Yes, the GPS data defining the target area received from his drone directs his tractor in the precision application of whatever is needed.

Drone proliferation

That was just a little taste of a single, very practical application of drone technology. But applications for this new resource are taking off, resulting in a drone population explosion.

The FAA is forecasting that 30,000 drones will be filling our skies within the next 10 years. Even this number appears to be a gross underestimate since amateur drone organizations report that today Do-It-Yourself drones alone are being produced at a rate of ~1000/month. And as with most newly available technology, we can expect that performance will increase rapidly, while price drops rapidly, fueling even greater rates of adoption.

Of course the number of government, specifically military, drones is also skyrocketing. And stories about them in the news are also multiplying. Often negative stories. So the term “drone” is getting a negative connotation in the minds of the public according to the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI). This drone industry trade association is actively advocating the replacement of the term “drone” with “unmanned aerial vehicle” (UAV) so that we’ll all feel better about them. But I’ll just call them “drones”, OK?

Extraordinary range of uses

As we might guess, there’s a huge range of drone applications already in use and under development.

Here’s just a sampling of some civilian govt. and commercial uses from Wikipedia: remote sensing, e.g. concentrations of radioactive materials in the air, commercial aerial surveillance, e.g. wildfire mapping, oil, gas & mineral exploration, e.g. geomagnetic surveys, transport, e.g. delivering goods directly to customer by drone copter, scientific research, e.g. data collection in hurricanes, search & rescue, e.g. search for missing persons, conservation, e.g. detecting and monitoring pollution. You can imagine many more.

Key uses for the military and intelligence agencies are of course surveillance and attack (at this time in Afghanistan, Pakistan and the Yemen). Law enforcement organizations are primarily using drones for surveillance, but also beginning to use them for armed attack.

And as for the private user … the consumer. Drones are already heavily used in an extension of what was once the model airplane community. But it’s the app-hungry smartphone/iPad user who will drive a truly wide range of applications. Because high-res cameras are standard equipment, surveillance will surely be an early major use. What are those neighbors down the street doing behind their wall, anyway? Well, you can just sit back sipping your latte, launch and find out by watching the action on your smartphone display.

Platforms

Drones currently range in size from large insect to 737 jet liner. And in configuration, they range from traditional aircraft to helicopter, to 4- or 6-rotor helicopter.

They all contain space and power for various payloads. In addition to electronics for telecommunication, navigation and control, there’s carrying capacity for sensors and weapons of many kinds (depending on space and lifting power). The Parrot drone pictured is 28”x28”, weighs less than a pound, is controlled by an iPad, iPhone or Android, includes downward and forward looking cameras, and is yours for $300 new ($250 or less, used) online, as of this writing. Wait. I just got hit with an Amazon ad, selling it for $237, new …

Strategy implications

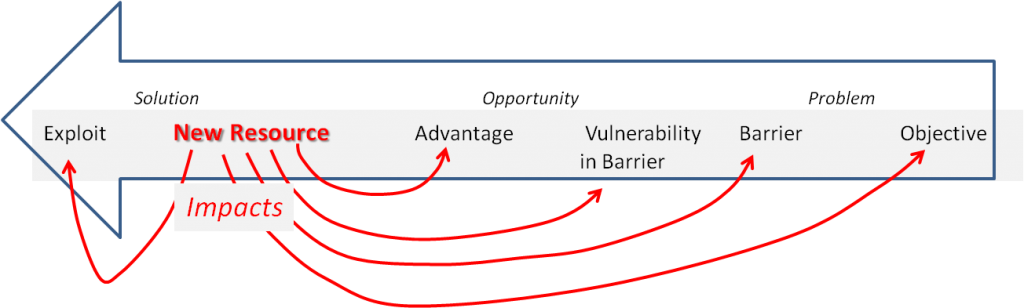

These newly emerged drones are a game-changing resource. From a strategy standpoint, a major change in a resource is inherently a big deal. Why? Because it impacts all other elements of strategies that can or do rely on that resource (as in the strategy diagram below). Only a change in an objective can have a similar range of impacts.

Suppose you win the TeraBux Lottery. The resource element of your strategy diagram is now bulging with money, and you can entertain an entirely new range of plausible objectives. Those have new barriers, which in turn have new vulnerabilities, which can be dealt with by new advantages that come with your new resource. And the new advantages can be exploited against the vulnerabilities in new ways. Similarly for the objectives you already had in place. Each kind of strategy element is affected. New ballgame.

And so it is when a significant new resource such as drones emerges. Our strategies for doing all sorts of things will be affected, as indicated by the range of applications described above. We’ll be devising new strategies by updating the strategies we already have and creating new ones, enabled by drone technology.

Some of the advantages in this new resource that will find their way into new strategies are that they:

- Can carry payloads into places and situations previously inaccessible or too dangerous for humans

- Can be operated from a distance

- Can be operated anonymously

- Can operate autonomously, by computer program, like a robot vacuum cleaner

- Can be undetectable

- Small size – microdrones

- Very quiet – with electric motors

- Can operate in cooperation with other drones

- E.g. in swarms

- Can be very fast

- Supersonic (Univ. Of Colorado, Boulder, drone project starting at Mach 1.4, going to Mach 2 or 3)

- Can be very affordable

The Iron Law of Exploitation

I think we can see right away that these advantages are double-edged. And that’s because

1) For every advantage, there is an equal and opposite vulnerability (see “advantage” in Anatomy of a Strategy), and

2) If there is an advantage/vulnerability, it will (eventually) be exploited. (The Iron Law of Exploitation, first defined here)

Count on it. The advent of a new resource cuts both ways. A new resource, for “better or worse”? No. For better and worse.

Better

Many positives can be seen in the range of uses described above. And there’ll be many more beneficial applications that we haven’t even imagined – no doubt about it.

Worse

Perhaps less obvious is the potential for many negative consequences: both unintended and intended. In spite of the dazzling potential of drone technology, there’s also a sobering side that needs to be borne in mind. Not doom-saying. Just saying …

Three big areas of concern are in privacy, national credibility and safety.

Privacy invasion

We’re particularly vulnerable here, because there’s no general guaranteed right of privacy in the U.S. Constitution or Bill of Rights. The closest we come is 4th Amendment wording limiting search and seizure to certain situations. That’s right. And this makes incursions into privacy much easier and more likely. No surprise that over time there’s been more government, commercial and private intrusion as effective spying technology and public use of electronic communications has increased.

It isn’t paranoiac to think that his trend will certainly be increased with the advent of affordable and effective drone technology. The Secretary of the Air Force Michael Donley has issued an extensive memorandum discussing the use of military drones in domestic missions. Donley says that drones may be used to “collect information about U.S. persons,” and that the photos that these drones will collect may be retained, used, or even distributed to other branches of the U.S. government as long as the “recipient is reasonably perceived to have a specific, lawful governmental function”.

What business has the AIR FORCE to spy on U.S. citizens? There’s already no shortage of government agencies actively engaged in domestic spying. We have the FBI. We have the NSA. We have the CIA. Is the Air Force feeling left out? Apart from the spy agencies, the Dept. of Defense has hundreds of drones deployed at many 10’s of existing and planned drone facilities throughout the United States, including a location near you – see map.

Both surveillance and attack drones are being deployed to these sites. Think about that. Good intentions in this program are insufficient and nearly irrelevant compared with the eventual negatives.

National credibility loss

The temptation to use drones for military purposes is easy to understand. And limited and controlled use of them is not fundamentally different from using manned aircraft for similar missions. But there are other outcomes that need to be recognized.

The way our use of military drones has evolved blurs the borders of morality and diplomacy, and sets very dangerous precedents, inviting similar use of drones by other countries and entities, against yet other countries and entities, including our allies and us.

We’re upending a long-standing diplomatic principle by attacking locations and people in countries we’re not at war with, without those countries’ permission. And the attacks aren’t just made based on definite knowledge of the location of important terrorist figures. They’re also made based on characteristics of groups that have profiles “similar” to known terrorists, and that analysts think may contain terrorists. This of course results in the collateral deaths of many civilians. According to a UN human rights report, roughly 20% of the people killed in drone attacks have been civilians.

Apart from the morality of this, and of ceding moral ground to our enemies, there’s the problem of blowback. The civilians killed where we’re using drones (Pakistan, Afghanistan and the Yemen) are tribal people. Revenging the death of innocent clansmen is high on their list of what needs to be done. How many U.S. military and NGO people will indirectly die as a consequence of killing tribal civilians during drone attacks? What are the political consequences of the loss of favor in these places, suffered by the U.S.?

Safety

The FAA simply isn’t set up to exercise control over the 30,000 drones it expects will take to the sky in the next 10 yrs. How many accidents will be occurring with that growing density? How many crashes in populated areas?

What about unintentional or intentional collisions with airliners? What truly effective and reliable safety measures over all these remote control aircraft can the FAA actually create and enforce?

Remote control of drones can easily be accomplished over long distances. An engineer at Boeing has already flown a drone over an MIT baseball field, from his office in Seattle, 3000 miles away. Using an iPhone. It’s predictable that inexpensive, very small personal drones, controlled by iPhone apps over long distances, will become commonplace.

There’s an important psychological problem that goes along with remote control: other things become remote, too, including operators’ sense of responsibility. Sense of responsibility decreases as anonymity and distance increase. E.g. U.S. military investigators found that “inaccurate and unprofessional” reporting of targets by U.S. operators in Nevada, of a Predator surveillance drone in Afghanistan, resulted in a missile strike that killed 23 Afghan civilians in February, and injured many more – men, women and children. Cowboys.

There’s a debate within the military today regarding awarding medals to the drone pilots, because they are under no threat and in no danger from the adversary they’re attacking. They aren’t going into harm’s way. The downside of making a mistake doesn’t put them at risk as it does warriors on the battlefield.

There’s been a major psychological shift in warfare. At one time, generals used to lead their armies into battle and fight alongside them. Then the generals abandoned the battlefield and left it to lower level combatants. Now the combatants themselves are abandoning it!

Removal from the battlefield and the personal risk that goes with it creates a videogame psychology. This is further reinforced by the controls used by military drone pilots: they’re modeled after PlayStation consoles (lower training costs). And because of drone proliferation, government departments and agencies are hiring young people as drone pilots as fast as possible.

Great: gameheads with their fingers on real triggers. Can this safety threat be managed through rigorous training? Across all those federal, state and local departments and agencies fielding a growing number of drones? Of course not.

Don’t get me started on autonomous drones with on-board processors that allow the drone to make decisions itself and take action based on the situation as it has sensed it, rather than being controlled by human operators.

And then there’s the safety threat from hacking. A legitimate drone doing a legitimate job, but someone hacks it and takes control of it for criminal purposes. Say terrorists. Couldn’t happen? A team at the University of Texas, Austin, received $1,000 from the Department of Homeland Security for demonstrating that they could successfully hack into an airborne drone and take control away from the pilot. But unfortunately the Dept. of Homeland Security accepts no responsibility for protection against drone hacking by terrorists or others.

Trust in God, but tie your camel first

The potential for this resource is so great that an explosion of applications, uses and number of drones will occur, affecting existing strategies of many kinds (commercial, military, personal …).

There will be a dialectic between those who wish to exploit the opportunities arising from this technology to the fullest and those who are concerned about the consequences of it.

The bulk of the applications will be positive, or at least benign. And it’s enough to trust the market to stimulate these beneficial uses of drones. But it’s not enough to trust the industry to regulate itself sufficiently to avoid the negative side of this new technology (the drone industry trade group – AUVSI – is already putting together an advertising initiative to counter legitimate but bad publicity about drones, regarding the key issues of safety and privacy).

Neither is it enough to trust the government to ensure that the negative potential of this technology won’t become part of a “new normal”, in the same way the legal sale of high-rate-of-fire fire arms did. The governed are going to have to be all over this and help shape what the new normal will become.

__________________________________________________________________

Readers are encouraged to add comments to this post.

And if you’d like to share or recommend the post, click on your preferred way in the left margin sidebar.

Stay tuned for the next post. It’ll be mercifully shorter than this one, and will be about Negotiation Strategy; Selling on the Silk Road (counterpart to the earlier post on Negotiating Strategy; Buying on the Silk Road).

If you’re not currently being automatically notified when new posts are published, then please Follow Real Strategy (top of right hand column on this page), and indicate how you’d prefer to be notified.

For other posts of interest, look in the Smart Menu.

Photo credit: Farmer’s Drone, Jake Putname, Idaho Farm Bureau Federation, Ag Weekly, http://www.agweekly.com/articles/2007/11/22/news/ag_news/news31.txt

Photo credit: French Parrot AR.Drone, Paul Goodhead, bit-tech, http://www.bit-tech.net/bits/2010/07/18/parrot-ar-drone-review/1

Photo credit: Predator Drone, Drone Wars UK, http://dronewarsuk.wordpress.com/2012/05/16/drones-as-military-use-expands-civil-use-being-developed/

Photo credit: UK Police Surveillance Drone, MailOnline, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-476748/Police-use-remote-controlled-drone-spy-crowd-V-festival.html

Photo credit: Ready for takeoff, Tom Frey, Da Vinci Institute, http://www.futuristspeaker.com/2011/03/the-day-of-the-drone/ (follow this link to encounter some very imaginative uses of drone technology)

Good essay. This is a topic I too have been researching. The potential, nay probability, for things to get completely “out of hand” is enormous. For those who believe otherwise I offer three sets of famous psychological experiments: Milgram; Stanford Prison; Asch Conformity (for those who do not already know about them, look them up).

Also, here are a couple of links that you might find interesting:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pxb-kgDapVU&feature=player_embedded#! [HD video FPV]

http://diydrones.com and http://www.rcapa.net

Related is the recent overturning of the Treaty of Westphalia and “replacement” with what has been (disingenuously) termed “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P). This has been used by the US and NATO to invade and overthrow countries (think Ivory Coast, Libya, and now Syria) under the rubric of “protecting the people” from terrible dictators! And “our” political psychopaths do it with straight faces.

Finally, your phrase (in part) “. . . .in the same way the legal sale of high-rate-of-fire firearms did” is predicated on assumptions on which I must call BS – and we can discuss at greater length another time. {;^) ~RR

[Translate]

Well, funny enough I just read a major news article on Yahoo about this this morning. Personally, I think this is an awful trend that has the potential to be disastrous on so many levels.

One amusing issue is how the gun control theme ties into the drone theme: A random check of a few hundred – of the more than 6 thousand comments to the Yahoo article – should the sentiment amongst article readers to be *extremely* negative toward the idea of domestic drones – and – the antidote agreed upon by all – was to use drones for “target practice.” I must admit that although not a gun owner or enthusiast myself, if I saw one flying over my back yard, I’d be tempted to take a shot at it myself.

There’s just something instinctually wrong about this that I think is not going to “fly” with most Americans, except perhaps those who are to naive or lazy to contemplate the numerous consequences that would be inevitable: flying drones into aircraft intentionally, domestic spying and control; eventual domestic “neutralization” technology (veering from science fiction to science reality), monitoring and controlling airspace without accidents ( I can’t imagine if drones “take off” that the public can just fly drones wherever and whenever they want – eventually it would have to be government and law enforcement only – disturbing – due to the sheer magnitude of safely managing airspace. Then we have an Orwellian scenario).

Anyhow…a trend that I hope never takes off

[Translate]