PUSHING BAZAAR

The largest market in Central Asia is the Pushing Bazaar in Ashkabad. Why ”pushing”? Because it’s packed with potential customers and onlookers, and you have to push your way through the crowd to get anywhere.

And once you’re there bargaining for something, if the action is interesting, people will push their way into the situation, offering their own assessment of the item’s value, and arguing with each other about it (in the Turkmen language – you haven’t a clue what they’re saying). It’s a pastime for them.

The place is huge, full of color, texture and sound, and is roughly divided into sections. Here’s a section for treadle sewing machines – large, heavy weight models from the former Soviet Union, ancient Singers, etc. Over there’s the section for vacuum cleaners. On and on.

I was there to work the “antique” section, which generally meant things like carpets, arts, crafts, and jewelry. Handmade articles of various kinds, often actually antique. It was a good market to buy in, and I’d found and negotiated what I was looking for.

Coincidence

But now it was time to get down to what I was really there for. My primary objective was to sell, not to buy. In the earlier part of our Silk Road trip, I’d focused on learning how to effectively negotiate there as a buyer, and had that under my belt. Now I wanted to play the other side of the game.

But unlike the merchants, I had no booth and no merchandise worth mentioning to sell. So how was I to get into a situation in which I could try my hand negotiating as a seller?

I was standing just outside the antique section, watching the crowd and searching for any clue about how I might do what I was there to do, when a woman emerged from the throng and came over to me. She wore a blue-patterned dress of the kind favored by women of the Tekke tribe.

In perfect English she asked if she could help me. I said that I certainly hoped so, but first – how was it that her English was so good? She said that she had graduated from Ohio State University. Oh, of course: a Tekke tribeswoman in the Pushing Bazaar in Ashkabad, Turkmenistan, who had graduated from Ohio State. Why hadn’t I thought of that?

I told her what I wanted to do. Without hesitation, she said to stay where I was and that she would arrange something.

In a few minutes she returned and asked me to follow. We pushed through the crowd (naturally) and came to the booth of some of her fellow tribeswomen who were selling silver jewelry.

Brief diversion: how do seemingly unlikely things like this encounter happen? Hard to say. But I like the word “coincidence” because it seems clear that some things are coinciding. Namely, trajectories. I wanted to do certain things, was on a trip to do them, had formed an intention to do something specific and was consequently on a certain trajectory. The woman helping me do this was on her own trajectory. Our trajectories briefly aligned and coincided allowing this unlikely connection to happen. Back to selling …

Jewelry Booth

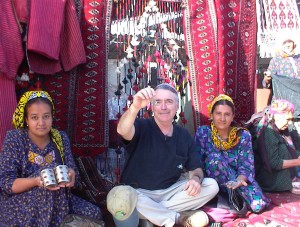

They were waiting for me in a typical booth consisting of carpets spread casually on the ground, backed by more carpets and fabrics hanging from a frame behind them, with their wares arranged artfully on the rugs. They had decided that any respectable male merchant in their booth should wear the traditional merchant’s cap and slippers with the pointed, turned up toes – and they had them waiting for me. The cap fit, but not the slippers (damn! – I’d have to stay in my North Face boots).

The women didn’t speak English, but my guide briefed me on some pricing ground rules (specifically walk-away prices). I would be able to hold up an item and say “First price X manat!” (manat = their currency) and from then on, as the negotiation proceeded, write the prices on a piece of paper and show it to the buyer. The women would describe the virtues of the jewelry I was selling and repeat the price in the Turkmen language. And that’s how we proceeded.

The novelty of an American tarted up as a Pushing Bazaar merchant and interacting with customers in this unusual way seemed to draw a pretty good crowd.

Silk Road selling strategy

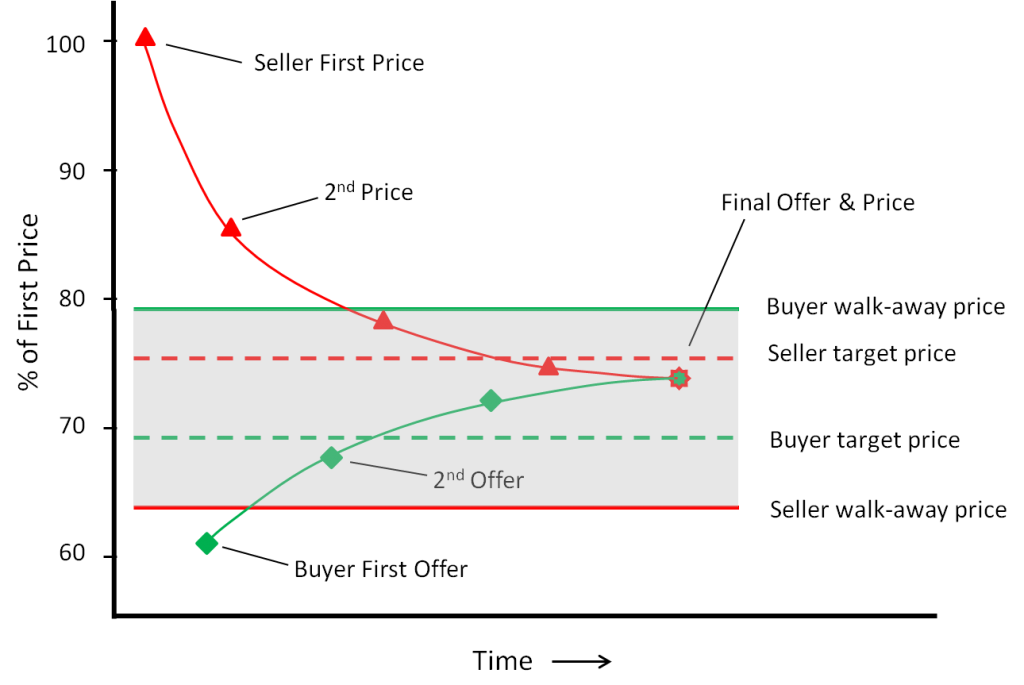

So what was the negotiation strategy? A previous post on buying strategy used the diagram below, and focused on the lower curve – representing the buyer’s offers. Here the focus is on the upper one.

As a seller on the Silk Road, I get to set the first price (that’s the custom there). This is an advantage because it psychologically “anchors” the prices and counter offers closer to a final price I want. I set it at about 25 – 30% above the target price at which I hoped to eventually sell the item. Enough wiggle room to negotiate, but not so high that it turned off potential buyers.

Then, based on what I had learned earlier as a buyer, I lower the price pretty quickly in response to the buyer’s offers – at first, to encourage them. But then level off quickly after that to signal that I won’t go much lower. This tests their will to keep offers low, and tends to force them higher, sooner. And that tends to ensure that I end up with a final price close to, and maybe higher than, my target.

All the while, the buyer and I are both obscuring our intentions, each creating a gray area for the other to try to see though, while making their moves. Meanwhile, the seller’s strategy is to control the rate of change of the price during the negotiation to guide the buyer to a final offer that’s near the seller’s target.

This, together with the buyer’s strategy described in the companion post lays out a good way to negotiate in places like the Silk Road. Both are based on rate of change of the prices or counter-offers, and both create trajectories that hopefully converge in a mutually acceptable final offer and price.

But this isn’t just for the Silk Road. These strategies work well for essentially any negotiations for anything, anywhere, as long as they take place over an exchange of several prices and counter offers.

End game

OK, so how did it go in the jewelry booth? Pretty well. I sold a few items for the ladies, and they seemed happy with the results. And then I bought some jewelry, myself. It only occurred to me afterward that this may have been their motivation for allowing me to play merchant for them in the first place!! As I pointed out in the companion post, the women merchants in Central Asia are really smart. In any case: win/win.

And that’s how it works, when it’s working, on the Silk Road.

_______________________________________________________________________

Readers are encouraged to add comments to this post.

And if you’d like to share or recommend the post, click on your preferred way in the left margin sidebar.

If you’re not currently being automatically notified when new posts are published, then please Follow Real Strategy (top of right hand column on this page), and indicate how you’d prefer to be notified.

For other posts of interest, look in the Smart Menu.

Hi Bill,

If you lower a price for a painting (in most cases) it signals a lack of respect for the art and the artist, turning it into a commercial transaction. Usually when a person asks me to lower my price it is usually an insult and they have no intention of buying.

Sounds like you were having a good time.

[Translate]

Interesting comment. Culture rules in these situations. In Central Asia, there are two points at which a seller (including artists) can be insulted. First, if a buyer declines to negotiate, and simply pays “first price”. This communicates that the buyer doesn’t find the seller interesting enough to engage with, and/or the buyer regards himself too rich/important to bother with such matters. In either case it diminishes the seller (as they see it). The second potential point of insult is when the seller offers first price. If the buyer counter-offers with 50% or less, it communicates that the buyer thinks the seller and his price are rediculous (as they see it). I recon insult is both in the ear of the beholder, and in the intention of the beheld, culture depending.

Setting prices as a seller and making offers as a buyer are definitely interesting problems – whatever the culture.

[Translate]

Welcome to another iteration of a truly free market.

[Translate]

Evidently little has changed in their way of operating for the last few thousand years, in spite of a recent communist past.

[Translate]

I love that sellers on the Silk Road actually say “first price!” when they announce the price of a product. There’s no ambiguity that the price is negotiable. In the West, people usually ask the price they want and then are disappointed if people try to negotiate them down. As a Craigslist seller, I’ve found that I often ask a tiny bit more than I want, expecting one iteration of negotiation. If the buyer takes my price without question, great. It leaves room for maybe one round of haggling, but nothing like the 6 or 8 step exchange in Central Asia.

[Translate]

Sounds right for Craig’s List. To each place it’s number of price/offer iterations and conventions about first vs. final price.

[Translate]

Hi Bill,

My number one bargaining strategy is that you have to not covet the item and be willing to walk away. they will usually chase you.

I hate to tell you this but number two learned and practiced in China was to start at 25% and never pay more than 50%.

[Translate]

Being willing to walk away is critical. And you have to mean it, so deciding beforehand on your walk-away price, is critical.

As far as lesson learned #2 is concerned, each place has its own conventions – and its best to know them before serious bargaining begins. But 25-50%? Surely you’d go for 55% – its a great car, hardly used, and I’m trying to put a kid through college.

[Translate]

I remember that “last price” is firm. One must be willing to walk away if that price can’t be met.

Then there is offering less for one object and full price for another, or full price if some minor object is included for “free”. Two items leave the inventory. That is a plus because then the seller can go on to another customer and the purchaser -while he may have less discount- can enjoy two items.

In Central Asia, we found that many sellers are willing to educate a customer about an item. For example, the Tajik embroidered mirror cover I purchased from a Russian seller in Samarkand… She told me how the item was used and why a mirror should be covered except when needed.

In some cultures, negotiating is the very fiber of societal cohesion. What is passed from one person to another is time and attention. Without this there is no life essence.

The seller telling a story about an old piece one has found gives the item a certain vibe. It’s as if a particular essence has been incorporated into the object via the transaction itself.

The medium for this transmission is the personal exchange.

In Bokhara, after purchasing our carpet, the merchant gave us a bonus gift: a donkey with Nasrudin, sitting backward, astride the animal. Indeed, in Bokhara there is a large bronze statue of Nasrudin.

[Translate]

Right – in Central Asia a negotiation is an exchange (a jam, as its sometimes called) and an exchange is much more than a literal transaction of a certain amount of money for a certain object.

[Translate]

Right, negotiation always has to have an element of good humor in it for both parties. It is a mini slice of a relationship. The Chinese did compliment me on my bargaining skills but I still think they often ask foreigners outrageous prices hoping to get a good portion of what they ask.

[Translate]

Good point about humor in negotiating – it moderates the adversarial aspect and puts the parties into a more person-to-person and less formal mode of interaction. The outrageous initial price is interesting. Even if the buyer summarily rejects it at the outset, it still psychologically lingers as an anchor point further in the negotiations. This is why the buyer’s setting and sticking to a target number is so important.

[Translate]

Thanks for drawing the connection between the words “coincidence” and “coincide”. Elucidating.

Good to know before hand the haggling habits in the culture you’ll be visiting. Helps to not end up feeling offended, or accidentally offending someone.

[Translate]

In a negotiation in Central Asia, it may seem that the currency is money. Well it is, to a certain extent. But the current passing between the people can be tangible or intangible. Time and Pomegranates.

[Translate]