BOURN POND

Its nice sitting in this tree. The sun has broken through intermittent clouds, switching on the brilliant leaves of my red maple. This is no ordinary tree. It’s a cage. The main trunk is normal for the first two or three feet. Then it splits into 5 sub-trunks that start horizontally for a couple of feet, then go straight up, creating a cage. Once inside it, your visual field is saturated red leaves. Gorgeous. The tree is on the shore of Bourn Pond in the Lye Brook Wilderness in southern Vermont; it’s the only place I’ve seen trees like this.

The wilderness area is on a high plateau in the Green Mountains. It’s in a hardwood forest, with some conifers mixed in. I like to come up here on solo backpack trips during the peak of leaf season. It’s great to pack in and hang out for a week, and watch what’s going on. A lot of color. A lot of wildlife activity. Moose in the morning. One afternoon I saw a fisher (a large black cousin of the weasel and marten, that moves over the ground like a sinuous black pool: strange to watch). A Kingfisher (unrelated) and plenty of waterfowl, of course, including the lonely loon.

Remnant arms of a hurricane that had rolled up the E. Coast were still heading north, clipping by overhead, and making for an alternately bright and dark morning.

As skim ice along the pond’s shore was melting back, I’d come down from my perch, pulled up a tree stump, and was warming my hands with a tin cup of hot tea, next to the water. Smokey lapsang souchong: great with the smell of Fall hardwood leaf litter.

Sitting there, something unusual emerged. A spider had tethered itself to a rock with a silk thread and was riding the surface tension of the pond. It seemed to be doing something systematic, but that’s all I could tell.

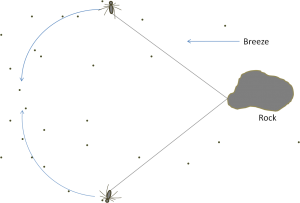

Take a look at the diagram. It’s a view of the scene from above. On the right is the rock.

The spider, supported by surface tension, is tethered to the rock by its silk thread. The same spider is shown twice: once in the upper and once in the lower part of the drawing. There’s a mild breeze coming from the right (the last gasp of that hurricane), keeping tension on the spider’s line.

In the upper position, the spider would cant its body by “paddling” to its right, relative to its tether. This caused the breeze to catch the spider’s body broadside and push it over the pond surface to its left and down in the diagram. When it got to the “bottom”, it would cant its body to the left, relative to its tether, picking up the breeze on its left side, which would move it back to its right and up in the diagram. It just kept skimming slowly back and forth this way.

Strange. What’s going on here? Other than humans, animals generally don’t waste time and energy on leisure activities. Spiders don’t have sports. So we have to ask why its spending its time & energy doing this. Why is it in its interest to do this? What’s in it for the spider?

Lying down on the pond’s edge to get a closer look, what spider business it was up to still wasn’t at all obvious. But when I changed my position to check it out from a different perspective, the new angle to the sun revealed that there were very small particles floating on the surface, and moving with the breeze (right to left in the drawing) through the region the spider was sweeping.

Watching the spider at that angle, it appeared that when it encountered a particle during one of its sweeps, it would pause and consume it. So all this sweeping behavior was to skim little morsels of food off the surface and have a meal (I have no idea what the morsels were – but I don’t think there are spiders that are vegetarians).

I’d seen spiders doing a lot of things with their silk threads, but never anything like this. And it got me thinking about the extraordinary range of spider adaptations that were enabled by their ability to produce silk.

Spider silk

Spiders show up on the fossil record about 450M years ago. That’s an M. They were here a couple hundred million years before the dinosaurs, and from their little nooks and crannies watched those Johnny-come-latelys arise, rule the Earth, and then disappear. All in a mere blink of a compound eye.*

About 40,000 species of spider have been identified. It’s estimated that there are probably that many more species, not yet recognized. And of course a vast number of species that have come & gone during their 450M year tenure on this planet. They’ve survived massive meteorite impacts, massive volcanic events, massive floods, massive ice ages – massive everythings.

They embody some of the most successful survival strategies in the history of life on the planet. And one of those strategies is to produce a general purpose material that can be used in a remarkable number of ways as a resource for pursuing other survival strategies: silk.

Each spider has around 7 nozzles for producing silk with different characteristics: tensile strength, toughness, flexibility, stickiness, etc. It allows many different species of spider, specializing in different ways of using silk, to arise, occupy an extraordinary range of niches, and survive. Including the wall of my study.

Most spiders use silk in several ways, but are known for a specialty. A wide variety of web traps, like the orb spider with its beautiful spiral web in your garden, or the black widow with its nearly random network of threads for a web. There’s the trap door spider that lays in wait for prey under its camouflaged silk door, and one of my favorites, the bolas spider that – like a gaucho – whirls a line around its victims (shown in action by Richard Attenborough in this video).

And did I mention the rare Lye Brook Wilderness Skimming Spider (surely number 40,001)?

Of course the silk’s not just used for catching prey. Most spiders use it for rappelling, either to break a fall (like the jumping spider, that isn’t into think-run-jump), or just to get from somewhere high to somewhere low.

Spiders use silk to make cocoons for their babies, and for wrapping their prey to set aside until it becomes tasty and ready for consumption.

And then there’s the sail. Just a very long piece of very light thread, sufficient for floating a baby spider over a long distance to a new home. Long distance? On multiple occasions they’ve been reported caught in sail boats’ riggings over a thousand miles from land. Carried aloft by thermals, these little guys with their sails have been inadvertently collected by research balloons clear up into the jet stream. You’re never safe.

Resource, the enabler

From this look at spiders we can see that having a good resource available is really important to enable strategies. Spiders have earned their hard-wired resource through eons of adapting to environmental change.

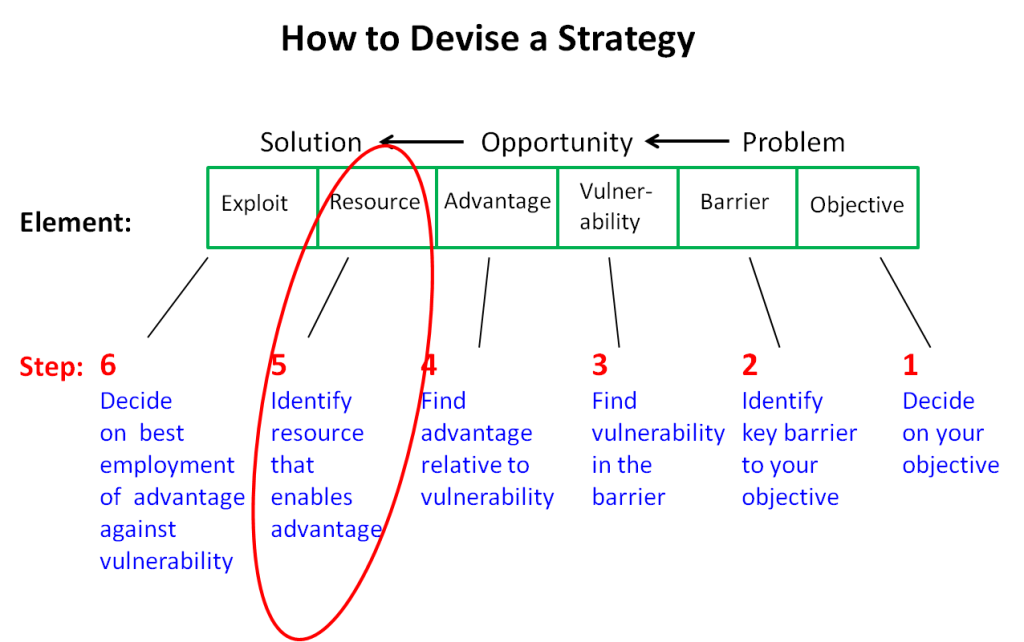

We’re late-comers, and don’t have an equivalent resource. But we do have the intellects and intuitions to recognize resources in situations that we find ourselves in, and to devise strategies that employ them. Let’s remember that resource is one of the 6 basic strategy elements.

Resourceful

Getting good at recognizing and basing strategies on them, is of course called being resourceful. And being resourceful is very much a matter of perspective and focus. Remember the strategy heroes in earlier posts: Nuvolari, the unnamed townsperson in Monsanto Portugal, Achim Weyer, Odysseus, John Thatch, etc. Being resourceful was a key part of their ability to devise the strategies they needed.

Time for some creative thinking.

OK, a dam has broken upstream, and while you’re not in the direct path of the wall of water, you have to quickly come up with a strategy for surviving in water that’s deeper than you are. You need a floatation resource, right now. What in the room you’re in at the moment can be used for one?

You look around with the idea of “float” in your mind, and set your intention on finding something that will work. You can quickly see several candidates.

A good sized box. A bunch of bubble wrap in the corner. A cushion. Your pants knotted at the end of the legs and wetted to prevent air escaping. An emptied briefcase. A side of a desk, torn away. A few shelves from a book case. A small table. An inverted waste container. Your lungs with a full breath. An emptied file folder case. A decorative drum. Once you switched your mind to “float”, you found that the place is crawling with resources. Now you can devise a survival strategy:

- Objective: don’t drown

- Barrier: own negative buoyancy

- Vulnerability in barrier: it’s the net buoyancy of you together with something else that really matters

- Advantage: You could hold onto something that was highly buoyant, so that together you would be net positive buoyant

- Resource: whole room full of highly buoyant objects

- Exploit: you decide to use your pants with the legs tied off, stuffed with the bubble wrap (the air can’t spill out or leak out of the bubble wrap as it could a box or briefcase, etc., the bubble wrap has more buoyancy than most other candidates and the pants can protect the bubble wrap from being damaged and loosing air, as well as providing something easy to hang onto).

That’s the strategy. And it’s clear that the resource was a key factor in shaping it.

Invoking the idea of “float” helped you to quickly see through the Gray Area and find what was needed to enable the strategy.

The good news is that resources are almost always there. As my gung fu teacher used to remind me, anything can be a weapon. It’s just a matter of being open to what’s possible in your situation.

Sometimes the situation can be very unfamiliar and it’s more of a stretch to identify useful resources. But whatever your situation, if you have a little time available, brain-storming and other creative thinking techniques will help you see what you need to see.

________________________________________________________________

* Just a metaphore. Spiders don’t have compound eyes like insects. They have multiple unitary eyes. And they certainly don’t have eyelids to blink with, either. Artist’s license. Or something.

________________________________________________________________

Readers are encouraged to add comments to this post.

And if you’d like to share or recommend the post, click on your preferred way in the left margin sidebar.

Be sure to catch the next post. We’ll be talking about defensive strategies, starting with The Great Wall.

If you’re not currently being automatically notified when new posts are published, then please Follow Real Strategy (top of right hand column on this page), and indicate how you’d prefer to be notified.

For other posts of interest, look in the Smart Menu.

Photo credit: Autumn in the Lye Brook Wilderness, by brianj922. Check out his photostream.

This, in some ways, is my favorite post. I like the comments about the ancient natural history of spiders and the reference to their having evolved a resource of such variability and effectiveness. And the pheromones! I’d no idea about that adaptive piece of hardware. All creatures, virus to human, evolve and adapt strategies for survival. But this is truly a marvelously resourceful class of critters, the arachnids.

[Translate]

I like this article. I thought I knew a lot about spiders and learned how little I actually know. The various strategies and tactics were the most interesting to me.

A great blog that I hope to share. Thank you.

[Translate]

Glad you’re enjoying the blog, Wayne. With all those spider species, the strategy variety is almost endless.

[Translate]