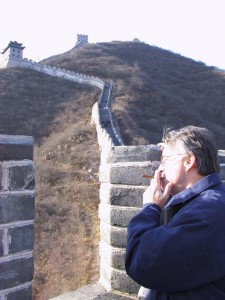

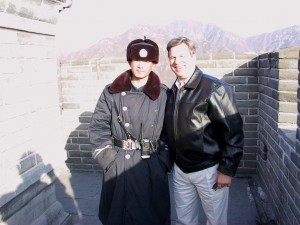

– Standing on the Great Wall with friend & colleague Guy after finishing up business in Beijing … You can get a sense for the unending and imposing character of the wall from the picture. The photo was taken just moments before the Great International Cigar Incident occurred.

Our private tour guide, Grace, had let us loose at the entrance to the wall stairs at the Mutianyu garrison. She knew what we were in for. We‘d targeted a specific guard tower high up on a hill as our goal. It was a really tough climb up the steps of several segments of the wall to reach it. But I’d brought along a nice little Havana cigar to celebrate achieving our goal, and had kicked back, and was enjoying the flavor and aroma. Ah, nothing like a good Havana. I stood there looking through crenellations at the wall crawling over the stark hills above us. Then I felt a tap on my shoulder.

A guard. What did he want? He was motioning to my cigar, and indicating that I should throw it down. Are you kidding? No way, Pal! I pointed out that it was just a small cigar and could pose no danger to the stone wall or the tourists walking on it. Maybe he would go away.

Instead, he became more and more insistent; more and more agitated. But I knew just what to say. I explained to him that it was from his sister country Cuba, hand made by one of his Comrades there, and that it would be an act of Communist solidarity between the great nations of China and Cuba if he were to allow me to finish it. Meanwhile, I’m puffing away, and he isn’t buying. Play for time, play for time. So I pointed out to him that it wasn’t just a cigar, but a sort of art form recognized by people in the West and now being adopted by the Communist Party elite.

This didn’t change his slightly puzzled expression, either. Perhaps the fact that he couldn’t understand a word of English diminished the persuasive power of my appeal. In any case he took that well-deserved little cigar from me, threw it to the guard tower’s stone floor, and crushed it under the heel of his Jackboot.

OK, he wasn’t actually wearing Jackboots, but should have been. And where was Guy during all this? Enjoying the situation a bit too much as you can see from the picture. This, friends, was my introduction to The Great Wall.

Great Wall history

The wall itself makes a strong impression. That’s because it was intended to be a psychological barrier as well as a physical one. Built piecemeal over more than 2000 years starting around 700 BC, it follows the terrain for 5500 miles, roughly east-west, as a bulwark against Northern invaders.

It was constructed from available materials, including stones, rammed earth, tiles, bricks or whatever, to a height ranging from 15 ft. on extreme slopes in the mountains to more than 25 ft in other places, depending on location and the period the section was built. It continued to play the role of a defensive barrier even into the 1600’s.

Adversarial and Defensive Strategies

In an adversarial situation, the adversaries of course have strategies (conscious or not). And those strategies, like all strategies, have one or more each of the 6 strategy elements: objectives, barriers, vulnerabilities in the barriers, advantages, resources, and exploits.

As an adversary, an important job is to undermine your opponent’s strategy, i.e. to tamper with its elements. Reduce his advantages, increase his barriers, diminish his resources, etc.

A defensive strategy is one that focuses on increasing the number and/or magnitude of an adversary’s barriers, and/or reducing the vulnerabilities in those barriers.

Barriers to an opponent can take many forms. They just have to impede his meeting his objective. For instance, in fencing, barriers to an opponent’s attacks can include an ability to block (parry) the opponent’s cuts or thrusts, good footwork to stay just out of reach of his blade, various forms of disruption of his attack and psychological factors … all barriers to an opponent’s objective of winning.

Two major benefits of a defensive strategy, whatever the context, are that

- It protects

- It buys time

The protection part is obvious, and buying time is important for at least a couple of reasons. First, buying time may allow you to outlast your adversary (remember the siege of the village of Monsanto). It may give you time to organize your own counter-offensive actions and/or allow you to wait for reinforcements. It also buys you time to put together even more defenses.

Like more walls. During the pre-Roman era, the average local Celtic chieftain didn’t have the building technology available to erect really large, strong walls. So for additional protection, they built 2nd, sometimes 3rd, and even 4th concentric walls, in conjunction with moats. Once the first one was in place, they had protection and time to proceed with the next, etc.

When in hilly European areas once occupied by Celts, such as England, Wales or Northern Portugal, it’s fairly easy to find and check out the remains of these old hill forts.

Chinks in the armor

But all forms of defensive strategy share some inherent weaknesses. One basic problem of defensive strategies is that they largely concede initiative and freedom of action to the adversary. That this concession tends to reduce odds for success can be clearly seen in statistics from modern sport fencing.

In world class saber fencing, about 50% of the hits are scored in attacks, 30% in counter-attacks, and only 20% from defensive ripostes after a parry (block). This speaks volumes about the advantage of initiative. In the photo, the saber fencer on the right has initiated an attack, but the fencer on the left stole the initiative by counterattacking into the attack at the instant the attacker began. In a sense, the fencers are fighting to own the initiative, and the freedom of action that goes with it. It’s very difficult for even an outstanding defender to win matches, let alone tournaments, because the odds so heavily favor having the initiative.

Another major problem with defensive strategies is they’re good only as long as they last. A defensive strategy may work very well for a long time, but can be made obsolete in a moment by an unforeseen development.

Here’s an example. During a visit to southern Wyoming, it’s nearly impossible to not encounter herds of pronghorn antelope. These animals have a speed- and endurance-based defensive strategy and are really fast. They’re way faster than their main predators, mountain lions and wolves. This was puzzling to biologists because nature is economical. They only needed to evolve to be just enough faster, rather than way faster. Why should a species waste so much energy? Then it all became clear. It was discovered that the pronghorn had evolved to outrun a N. American cheetah that died off about 11 thousand years ago. Since then, it was Fat City for the pronghorns. Nothing could touch them. Nothing.

Until literally out of the blue came an even faster predator. The golden eagle. It had occupied the same region as the pronghorns for a very long time, but then one day an innovative eagle sensed that it could bring down a pronghorn by diving onto its back and sinking in its talons (just like it already did with another speedster, the jack rabbit), and then chasing it until it bled out and could no longer run. The strategy worked. Being intelligent generalist predators, other goldens nearby quickly learned the same strategy, which then got passed on to more distant groups. And it’s now a new-old ballgame for the pronghorns, whose defensive strategy is again being pushed to the limit. Just when you think you’re safe.

History is littered with obsolete defensive strategies. The French Army created the Maginot Line, a massive line of defensive structures along the border with Germany, designed to withstand any attack that could be made by tanks or bombs. North of there, at the border between Belgium and Germany, the Belgians had constructed a similarly impregnable barrier: the fort at Eben Emael, that blocked a route across the Albert Canal that could bring the Germans through Belgium and into France. Between these two defensive positions was the Ardennes Forest, obviously too dense for German Forces to penetrate.

The Germans wanted to cross the Albert Canal at Eben Emael, alright, but as a feint to draw the main French and Allied forces north. In a remarkably similar development to that of the pronghorns, the factor that made the Belgians’ defense obsolete came out of the blue: German gliders landed on top of the fortifications. The gliders were full of well-trained special ops troops that attached and detonated highly explosive shaped charges on the gun emplacements threatening the bridges over the canal, and completely disabled them. German tanks raced over the bridges. The French and Allies were drawn to the North.

And what about the famed Maginot Line? While the Allied forces were engaged further north, the Germans did penetrate the Ardennes Forest , and sent Panzer tank divisions through the Low Countries, in both cases ignoring the Maginot Line, which just sat there. Possessing the initiative and relative freedom of action, the Germans drove clear to the English Channel in 5 days; in a little over a month, they took Paris.

Today one of the facilities on the Maginot Line has been further hardened and is used as a French Air Force command center. Otherwise, pieces have been privatized as wine cellars and mushroom farms, and the rest left in decay.

And so it goes: castle walls meet gunpowder, immune system meets newly evolved auto-immune disorder, computer firewall meets latest hacker malware, electoral system meets superpacs, deeply entrenched PC industry meets smartphones, etc. Eventually every defensive strategy meets its match.

Balance

Sometimes we have no choice but to adopt a defensive strategy: sometimes no offensive strategy is available. Hacking, for example. I have no choice but to buy Norton software and services (or equivalent) to protect my PC. There’s no practical way that I can go after the hackers and stop their mischief, myself.

But usually we can approach adversarial situations with a mix of defensive and offensive substrategies. In a balanced strategy, the defense leverages the offense and the offense leverages the defense, providing a synergy in which the effectiveness of both is enhanced.

If you are a National Football League head coach, putting together a relentless offense can wear down your opponent’s defense, making it progressively easier to score against them. And the resulting higher score by your offense gives your defense a lead easier to defend, making it harder for the opponent’s offense. And if you put together a tough defense, it can wear down your opponent’s offense, making it even easier for your offense to stay ahead. Each leverages the other.

We sometimes hear that “The best defense is a good offense”. It isn’t. But coupling good defensive substrategy with good offensive substrategy always gives you something to work with. And that gives you a shot at meeting your objective.

____________________________________________________________

Readers are encouraged to add comments to this post.

And if you’d like to share or recommend the post, click on your preferred way in the left margin sidebar.

If you’re not currently being automatically notified when new posts are published, then please Follow Real Strategy (top of right hand column on this page), and indicate how you’d prefer to be notified.

For other posts of interest, look in the Smart Menu.

Photo credit: The Great Wall of China by Guy Wagner, www.rmlabs.com

Photo Credit: Hill Fort, England, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hill_fort

Photo credit: Counter Attack, from Sulekha.com, http://newshopper.sulekha.com/china-asian-games-fencing_photo_1612739.htm

Fun stories! Great photo of the fencers, too. I keep wondering if you’re going to discuss lateral thinking as a way to develop strategies.

[Translate]

Good question. Yes, at some point I’ll discuss lateral thinking and other creative thinking techniques as ways of developing the most promising strategy elements, and critical thinking techniques as a way of critiquing them to end with effective and/or efficient strategies.

[Translate]

My understanding is that the idea that “the best defense is a good offense” has been the assumption behind military exploits such as Viet Nam, in which case we rationalized our involvement with the thought that we were protecting ourselves against the domino effect of country after country going Communist, eventually threatening us.

Where and when did the idea that “the best defense is a good offense” originate?

[Translate]

I don’t know where the “best defense is a good offense” idea originated, but it’s been around for a long time. Surely the advantage of having the initiative didn’t escape early generals. But a literal-minded view that all you need is a good offense is really naïve.

The French planning for WWI was completely offensive and relied on what they liked to think was superior “elan vital” (life force or fighting spirit) of the French fighter (vs. the German). It didn’t quite work out as planned. So the plan for WWII swung to having a big focus on defense (Maginot Line, etc.). Didn’t work out too well, either. Generally, it takes both, deployed in a way that the resulting synergy confers substantial exploitable advantage.

I think characterizing our attack on N. Viet Nam as an example of intending to provide a defense within the domino theory is definitely right.

Today’s form of “best defense = good offense” is called the “Shock and Awe” doctrine. Use our high-tech advantage to hit them preemptively so hard, so fast, and so decisively that it’s all over before they have a chance to hit back. Game over before the other side can play. Like Iraq. Seems like all offense. But looking more closely, there’s lots of defense integrated with the offense. First we come in with stealth aircraft that are designed to be undetectable by radar, infrared, etc., as a defense against detection and destruction. With these, we knock out their command & control capability with the defensive objective of disabling their ability to shoot missiles at us, maneuver their troops against us, etc. Underneath the shock and awe bravado, there’s really a lot of enabling defensive strategy at work. As well there should be.

[Translate]

I am in complete awe at your ability to manipulate concepts in such clear and definitive manner. All I can add to the conversation is to observe that for a turtle to withdraw completely into its shell is onlya good defense if it first ascertains that it is not on lake-ice sufficently strong to turn into an ice hockey rink.

[Translate]

Thanks Gene – I’m glad to be back doing this. As for turtles: “Just when you think you’re safe …”

[Translate]