CRIMEA – News articles relating to Russia’s Crimea takeover have been unrelenting for the last month or more. As well, there’s been much concern about potential incursions into other parts of the Ukraine, and for that matter, other former Soviet countries.

A number of different actions and counter-actions have been reported, and many interpretations of the situation have been put forward. But what do these moves really signify?

Something we can call the Ratchet Strategy.

Just a little history

To understand how and why this strategy is being employed, we need a bit of context. Then we can talk about the mechanics of the strategy.

Because of its many attractions, Crimea has been a coveted prize of conquerors through the ages. In fact Crimea was conquered and run by at least 18 different ethnic/political groups before Russia took over its rule following the defeat of the Ottoman Turks (check out the list of early Crimea owners at the end of this post, if you’re curious).

But it’s also important to note that while there have been so many different contributions to Crimea’s culture and genetic pool over the eons, there is indeed a special connection with Russia.

Very important among the historical Crimean owners was “The State of Kievan Rus” (think Kiev, capital of the Ukraine). This is the same 9th – 13th century political entity from which Russia also arose; so there is a strong and ancient common political and cultural identity here among Russia, the Ukraine and Crimea.

Russia having been the dominant power in Crimea since the 18th century, complete with a large majority population of ethnic Russians, naturally has a strong sense of ownership.

Couple this with the strategic importance of Russia’s ice-free naval ports there and it’s not hard to understand Russia’s sense that Crimea’s going to the Ukraine instead of Russia after the breakup of the Soviet Union was a wrong that needed to be righted. Not least in the mind of the guy driving the Crimean take-back.

Putin

Putin, the man behind the strategy, is a product of the Cold War KGB – as are the people he’s surrounded himself with. He and they are most comfortable operating in an adversarial relationship with The West, whom they regard as The Enemy.

He believes that the breakup of the Soviet Union was, in his words, “the greatest political catastrophe” of the 20th century. And he dearly wants to be the strongman who returns Russia to its former glory of being a superpower.

But Russia is economically, and even militarily, somewhat weak; and its leaders know they can’t just rush in, decisively win a major battle and reconstitute much of the former Soviet Union in the hoped-for return to superpower status. They need to take another path and to take it one step at a time.

The ratchet mechanism

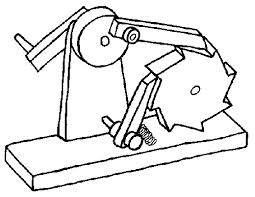

They need to move toward their objective like a ratchet. Check out the ratchet drawing. As the crank is rotated one cycle clockwise, the pawl attached to the wheel pushes on the gear tooth, moving the gearwheel to the right one increment. Meanwhile the lower spring-loaded pawl drops in behind a gear tooth and prevents any backward movement of the gearwheel. The next full rotation of the crank moves the gearwheel one more increment, etc. This is a mechanism that provides for controlled incremental movement only in one direction. The ratchet strategy is embodied in this physical mechanism, and it’s just the kind of strategy that Russia needs and is using to meet their regional expansion objectives.

They need to move toward their objective like a ratchet. Check out the ratchet drawing. As the crank is rotated one cycle clockwise, the pawl attached to the wheel pushes on the gear tooth, moving the gearwheel to the right one increment. Meanwhile the lower spring-loaded pawl drops in behind a gear tooth and prevents any backward movement of the gearwheel. The next full rotation of the crank moves the gearwheel one more increment, etc. This is a mechanism that provides for controlled incremental movement only in one direction. The ratchet strategy is embodied in this physical mechanism, and it’s just the kind of strategy that Russia needs and is using to meet their regional expansion objectives.

Ratchet strategy in the Ukraine

Russia is executing a ratchet strategy consisting of a succession of incremental steps, primarily based on pretexts such as removal of the Ukrainian president, Ukrainian nationalist threats to the ethnic Russian population, etc:

- Renewal of agreement to base Russian Navy ships in Crimean ports

- Pro-Russian protests by ethnic Russian Crimeans

- Blockading of Ukraine naval bases in Crimea

- Blockading Crimean border crossings

- Deploying troops to Crimea, taking over various military bases

- Instigating a Crimean referendum to become part of Russia

- Annexing Crimea

No one move exceeds the threshold of tolerance of Russia’s adversaries. Each step becomes a fact on the ground and after a little while, establishes a new normal (sometimes even codified in law), preventing reversal of movement. This was the same script used by Putin in the Georgian territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, except that it established protectorates instead of annexing.

At the time of writing, it’s not clear what may be next in Putin’s step wise strategy. There are currently some 40,000 Russian troops on the eastern border of the Ukraine.

And no shortage of pretexts for using them to “protect” ethnic Russians in other parts of the Ukraine. For example, the protests by ethnic Russians in the eastern city of Donetsk could spark bloodshed that could be used as a pretext for Russia to invade to prevent them from being harmed.

Of course there are other expansion targets, such as the little country of Moldova, jammed between the Ukraine and Romania.

So what is to put the brakes on Russian annexation of other countries – in whole or in part? Cost. From the very start of Russia’s move into Crimea, The U.S. and other Western powers made it clear that they would ensure that taking Crimea would be at real cost to Russia – to the nation’s economy, to its credibility as an international partner, and to the individual Russian leaders responsible for taking Crimea.

So Russia is making its calculations before taking another turn of the ratchet wheel. Some countries, such as Germany, are timid about applying heavy sanctions, because of their own economic dependency on Russian fuel, and their fear that Russia would cut them off. But they seem to forget that Russia’s economy is even more heavily dependent on exporting oil & gas to Europe, than Europe’s economy is dependent on importing it. It’s fair to assume Russia wouldn’t slit their own economic throat by cutting off those exports – at least not for long.

We’ll see. But what is certain is that Russia has a ratchet strategy in place for returning to previous glory as a superpower, and will continue to use it if the perceived cost to them is not too high.

Ratchet strategies, broadly

By now I’m sure you must be asking yourself how the geographic dispersal strategy of wild barley, the advent of mini mills in the steel industry, and the desert night warming strategy of Arabian camels are like the expansion strategy of Russia, right?. I thought so, and fortunately you’re reading the right blog post.

Foxtail– Just look at the picture of the wild barley foxtail, bane of long-haired dogs. It even looks like the embodiment of a ratchet strategy. It penetrates the fur of a passing animal that rubs by. Because of its shape, activity of the animal causes the foxtail to inexorably move in the direction of its point, bit by bit through the animal’s fur, never moving backward, until it finally works its way out and falls off after the animal has moved to some other hopefully distant location.

The seeds germinate; the species has spread out further, and has a greater probability of surviving. Nice use by nature of the ratchet strategy.

Mini Mills – The ratchet strategy is applicable in a very wide range of situations. Here’s a case from business: the encroachment of new, lower cost steel making technology into the markets of traditional steel makers.

In the ‘70’s, new “mini mill” companies such as Nucor, using new steel-making technology, were just starting to appear on the radar screens of traditional steel-making behemoths such as Bethlehem Steel. The mini mill companies used relatively small electric furnaces to melt local steel scrap to produce low end steel products such as rebar, usually sold locally/regionally – and sold really cheaply.

This part of the market had the lowest profit margins for the large steel makers, and potential loss in that segment was not a concern. Happily for Nucor, who was trying to avoid being crushed, Big Steel yawned and went back to sleep. The big guys could have easily created barriers to entry for Nucor, but failed to do so. Over time, the mini mills sophisticated their manufacturing processes and were able to produce much more complex products, such as I-beams and other formed structural materials.

Well, these products weren’t very profitable to the large steel makers, either, and besides, Big Steel was paying more attention to highly efficient Japanese competitors using traditional technology. So the mini mills grabbed big market share in more profitable steel products used by the construction industry. Another click of the ratchet.

Able to now invest in yet more sophisticated manufacturing equipment, mini mills subsequently went after and successfully penetrated steel’s crown jewel high-profit –margin market: the automobile industry. Fait accompli. Using this ratchet strategy, Nucor has become the largest steel company in the U.S. (also the largest recycler of any kind: one ton of scrap metal every 2 seconds).

We can see that the ratchet strategy can be used in almost any situation in which adversaries will accept a sequence of tolerable modest sized moves.

Camel – One last example. What about the chilly camel? An ancient Arabic cautionary tale, dating at least back to the 7th century, tells the story:

A Bedouin, making a long desert trek, pitched his small black tent and lay down to sleep. As the night grew colder his camel woke him up with a nudge. ‘Master it is cold. May I put my nose inside the tent to warm it?’ The traveler agreed, and settled down to sleep again. Scarcely an hour had passed, however, before the camel began to feel colder. ‘Master, it is much colder. Can I put my head inside the tent?’

First his head was admitted to the tent, then, on the same argument, his neck. Finally, without asking, he heaved his whole bulk under the cloth. When he had, as he thought, settled himself, the Bedouin was lying beside the camel, with no covering at all. The camel had uprooted the tent, which hung totally inadequately across his hump. ‘Where has the tent gone?’ asked the confused camel. (from Caravan of Dreams, Idries Shah, Octagon Press).

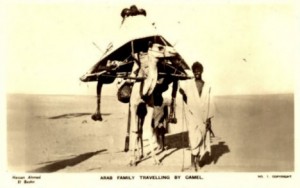

Incremental movement in one direction only. Clearly a ratchet strategy on the part of the camel. But how to prevent more encroachment in the future? Cost. Our Arab friends figured out how to arrive at the appropriate cost/benefit ratio for the camel: “You want to get under the tent? I think we can arrange that!”

________________________________________________

The Provenance of the Province: Crimea’s succession of owners

Groups who successively conquered, took over and ran Crimea in its long history are:

Cimmerians, Greeks, Phoenicians, Persians, Romans, Goths, Huns, Bulgars, Khazars, The State of KievanRus, Byzantine Greeks, Kipchaks, Ottoman Turks, Golden Horde Tatars, Mongols, Venetians, Genovese , Crimean Khanate, Ottoman Empire, Russian Empire, Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic within the Soviet Union, Germany during World War II, The Ukraine again until a few weeks ago, and today Russia.

The length of the list testifies to the high value placed on this real estate through the millennia.

_______________________________________________________________

Readers are encouraged to add comments to this post.

And if you’d like to share or recommend the post, click on your preferred way in the left margin sidebar.

Stay tuned for the next post.

If you’re not currently being automatically notified when new posts are published, then please Follow Real Strategy (top of right hand column on this page), and indicate how you’d prefer to be notified.

For other posts of interest, look in the Smart Menu.

Photo credit: Crimea Quick Look, AFP International News Agency, www.afp.com

Photo credit: Ratchet Mechanism, Mechanical Toys, http://www.mechanical-toys.com/ratchets.htm

Photo Credit: Foxtail, Curtis Clark (Cal Poly Pomona), Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foxtail_(diaspore)

Photo credit: Camel’s Nose, anon.

Photo credit: Camel Under Tent Solution, Bette, Gelean’s Grove, http://gelean.tripod.com/working.html

__________________________________________________

I LOVE the Camel in the Tent story. Just as good is the image of a solution, posted below the story.

[Translate]

I really liked the image – and the concept – too.

[Translate]

As you’ve described the ratchet strategy here, I recognize its importance to magicians, con artists and others who incrementally lead their audiences, victims, etc. astray.

[Translate]

Right! Each step may seem a little odd, but is below the threshold for rejection, and is accepted, so the end result is accepted. But taking the steps altogether, the thing as a whole is absurd or unacceptable. On the old ’70s TV show, Candid Camera, they would take unsuspecting people through a sequence of steps, each of which was a bit unusual, but didn’t in itself set off any alarms. But after several steps, what they were doing was truly ridiculous – at which point a voice would say “Smile, you’re on Candid Camera”. And the participant/victim, who had probably seen many episodes of the show, would realize they’d been had.

[Translate]

The metaphor of the ratchet mechanism is very helpful in visualizing how, once moved forward, it can’t move back. That is, unless a great deal of reverse force is applied that would bend or break the pawl. When the West exacts a cost on Putin, it corresponds to this reverse force, and that is why it may be hard to imagine the “costs” imposed would ever cause Putin to backtrack.

If, instead, the “costs” are actually some break applied to the handle so it can’t be turned, then the mechanism would have to be elaborated to show a drive shaft on the toothed gear that moved the whole thing in some direction. That’s the missing feature – the direction or purpose to which this ratchet machine is applied. Otherwise the reader, assessing the West’s counter strategy, will get no help to imagine how “costs” will ever stop this machine.

[Translate]

Yes, Mr Smith, your comment is very erudite, but fails to take into account the wave theory that describes the Higgs boson in motion and the influence of antimatter, all of which leads to the conclusion that this too shall pass.

[Translate]

It didn’t occur to me to incorporate quantum physics into strategy models …

[Translate]

Thanks for your observations, Tom. I think I could have been clearer about this. In the ratchet model, the cost (not shown) isn’t part of the ratchet; rather, its external and intended to dissuade the cranker from cranking another step. The pawl preventing movement backwards consists of whatever is resisting movement back to a previous state; for instance facts on the ground that become incorporated into an accepted new normal, as is the case in the takeover of Crimea.

[Translate]

The psychological incrementalism you outline in your Candid Camera example seems to be one of the archetypes of the art of persuasion predating the appearance of hominids. The secret to its success seems to forcing one’s opponent further and further into a situation where his agreement makes it impossible to retract his agreement without serious loss of face. Man the Toolmaker has, of course, added all sorts of instruments to make the persuasion more persuasive: the invention of nuclear weapons in political situations and the opening of a second bottle of wine in romantic ones. What is most amazing to me is that human thought could invent the physical ratchet to exemplify the mental process.

[Translate]

Thanks, Gene – very interesting comment. I’d definitely think as you do that the psychological ratchet preceded the physical one – probably by quite a long time. Not really sure what the earliest physical ones were, but would guess at least several hundred BC for use with siege engines in China, or maybe way earlier in lifting large objects without backsliding in the making of monuments.

[Translate]

Right here is the right web site ffor anyone who wants

to understand this topic. You understand so much itss almost

tough to arue with you (not that I actually would wannt to…HaHa).

You definitely put a fresh spin on a topic that has been wrtten about for many years.

Wonderful stuff, just great!

[Translate]

Thanks Gabriel – glad you like it. It’s been a couple of years since I’ve written a post (am working on a couple of strategy books), but I hope to start writing posts again before too long.

Regards,

Bill

[Translate]

This excellent website certainly has all of

the information I wanted about this subject

and didn’t know who to ask.

[Translate]

Thanks for some other great post. The place else

could anybody get that kind of information in such an ideal approach of writing?

I have a presentation subsequent week, and I’m on the search for such information.

my homepage v9bet

[Translate]

Thanks for your comment. Best wishes on your project.

[Translate]